Welcome back to my semi-regular roundup of anthropology-related happenings. Here’s what I have for you this time around:

1) Now is a time for Bundt cakes

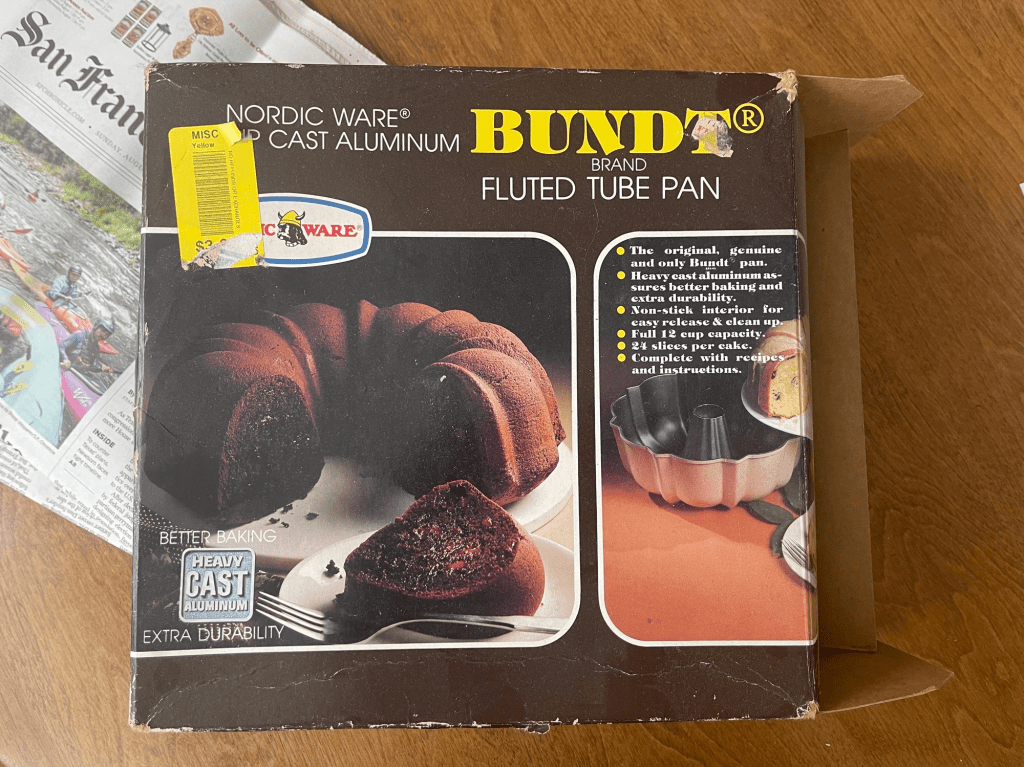

Considering all the madness in the world, the logical place to start here is with Bundt cakes. I was cleaning out our garage this past month and I happened across a classic specimen of a Bundt cake pan that looked like it was straight from the 1970s or 1980s (see photo above). Check out that brown tone on the box! That’s some exquisite old school brown right there. Amazing. I feel like this is something that one of William Rathje’s classes must have found in their excavations (along with all the paper and spoiled meat). I have no idea where this bundt cake pan came from or how it ended up in our garage. I think it may have been picked up in a yard sale or thrift store by a family member and then passed along to us. It’s so interesting how these pieces of material cultural end up getting passed around, stored, and (sometimes) rediscovered. Things just move around and they leave a trace of our lives, connections, and serendipitous decisions. This reminds me of James Deetz’s argument about all those ‘small things forgotten.’ These things outline our lives, and sometimes they show up at just the right time. I immediately notified Martin Pfieffer about this find since he’s the resident anthropologist/bundt cake expert. His response: “IT IS A SIGN! IT IS A GIFT!” What sign, you ask? When things go sideways (and this is happening a lot these days), take some time off and make some cake. Especially if it’s round.

Speaking of serendipity, there must be some kind of bundt cake resonance happening right now, because I checked the social medias and saw this. Straight from NYT columnist Jamelle Bouie: “When life gives you lemons…make a lemon pound cake in a bundt pan.” Martin was on it too. And he also kindly sent me a solid recipe so my household can get to bundt-caking as well.

2) What is this ‘gathering’ you speak of?

Now, let’s talk about magic. No, not some sort of Frazerian discussion about sympathetic or contagious magic; I’m talking about real magic. You know: the card game. Some of you may or may not know that the title of this roundup series (Anthropology the Gathering) is a nod to the game Magic: The Gathering (aka MTG or just ‘Magic’). If you haven’t heard of it, well, it’s kind of a thing. I didn’t know anything about it until the pandemic.

MTG was introduced into my household during the pandemic thanks to a friend of mine who has kids the same age. Since we were playing Pokemon he thought we should also know about Magic. I played a lot of Pokemon with my kiddo during the first months of the pandemic to pass the time, and then we learned about MTG and it was like the next step up. It’s a great game. I won’t get into the debate about whether or Magic or Pokemon is better.

Anyway, I was wondering if any anthropologists have written about MTG and, indeed, they have. Where did I find something? At The Geek Anthropologist, of course. Steven Dashiell wrote a piece in 2016 about narratives and storytelling in Magic: The Gathering. Here’s a bit from the conclusion:

Research on gaming such as this not only reaffirms the value of a gamer geek culture, but stresses the complexity of subcultural interactions. The narratives created by players are a mesh between a mastery of the game, a recognition of the audience, and an experience with talecraft.

In my household, with two young kids, MTG and Pokemon were two things that helped us make it through some of those very long days. I played a lot of both with my oldest…and those experiences made me think a lot about the value and meaning of playing such games, especially during difficult times. It feels sort of naive and quaint to be writing about a card game, considering everything that’s going on these days. But, then again, that’s probably why such games–and the time we spend with people as we play them–matter all the more. My title of this series is an homage to the power and meaning of gathering anthropological things, events, and people that matter. Now you know.

3) Sapiens is dead

In the not-so-great-news department, the anthropology magazine Sapiens is going to be closed down. As if we needed LESS anthropology out in the public sphere! Here’s the announcement from late July. It was a great project that produced a lot of content that I often used for classes (and just for sharing with non-anthro folks), and it’s sad to see yet another public-facing anthropology site close down. What happened? Long story short, the Wenner-Gren lost its publishing partner and could not find a replacement, so the project had to be closed down. It’s a shame and we’re left with even less anthropology out in the public sphere than we had before. All I’ll say here is we may need to find ways to keep anthropology out in the public sphere, at least in part, with low-cost methods that don’t require large publishing grants or partners. We may need to find a thousand or a million little ways to get anthropology out there.

4) On free speech, protest, academic freedom, and repression at universities

Louis Römer published a response to Alex Gourevitch’s essay on “The Right to be Hostile” in the Boston Review. Römer’s response is titled “Liberal ideals are being exploited for anti-left repression.” Here’s the intro to his response:

Alex Gourevitch mounts a welcome, vigorous defense of the right to protest. But while he correctly traces how the preoccupation with safety in the United States led to narrowing the scope for legitimate protest, he largely misses the role that opportunistic appeals to “free speech” have themselves played in that process. The latest deployments of “safety” arguments are part of a longer-term pattern of anti-left repression that exploit liberal ideals of freedom and safety for political, indeed partisan, ends.

Read the rest here.

5) Anthropology and repression ‘back in the day’

Speaking of academic freedom and repression, thanks to Adia Benton I learned a bit more about Gene Weltfish’s story and treatment at Columbia University (via this piece). I didn’t know much about this particular episode in our disciplinary history…but it’s sadly as relevant as ever. If you don’t know, the short version is that Weltfish was turned in during the 1950s, had to testify before the House un-American Committee, and essentially had her career destroyed. One particularly damning point is that Weltfish was actually turned in by her department chair, Ralph Linton. So much for academic freedom. Here’s a selection from the essay:

Although Columbia University presidents and trustees maintained during the cold war that the university protected its professors from McCarthyism, the case of Gene Weltfish proves otherwise. In 1952, Weltfish was called in front of the House un-American Activities Committee, and a few months later the university dismissed her under a shady rule recently created by University President Grayson Kirk and the trustees. Although she did have ties to communist groups, Weltfish denied any personal sympathies with communist causes and distinguished herself in the Anthropology department with her academic work. Her case shows how, when faced with a professor who spoke publicly about views that aligned with communism, the University gave into the same sort of McCarthyist tendencies it publicly criticized. Worst still, President Kirk did so under the guise of “academic freedom,” stating that Weltfish’s dismissal protected academic freedom.

Here’s the link to the whole essay in case you don’t feel like scrolling up and looking for it again. Also note that David Price had a whole chapter about Weltfish in his 2004 book Threatening Anthropology.

6) Biology and binaries

Kate Clancy, Agustin Fuentes, and their co-authors won an Apex Award for Publication Excellence for their article “Biology is not binary.” One of my favorite points from this article is this one:

Few of us even know for sure what gonads, chromosomes, or hormones we have. In fact, it’s not exceptional for people to accidentally find out they are intersex through fertility evaluations, genetic testing, or other medical tests or procedures. The number of intersex people is likely much higher than estimates indicate because of the over-dependence on genitals as the primary means of defining and categorizing people via sex (Clancy et al. 2024: 81).

Plus there’s this great closer: “The truth is, sex is defined a lot of ways in science, but in none of them should individuals who are part of nature be ignored and excluded. That would be bad science.” Indeed, it would.

7) The Democracy Problem

It’s interesting to think about how Americans talk–and think–about the idea of democracy. I think a lot of folks tend to believe that the system if more democratic than it is (or was ever meant to be). Especially because many elements of the US system are actively anti-democratic or limit actual democratic participation. We’re currently seeing the limits and weaknesses of this system being pushed to the edge (particularly when it comes to executive power but also with issues of democratic representation more broadly). Along these lines, here’s an extended passage from David Graeber’s The Democracy Project that I think about a lot:

The American War of Independence had been fought in the name of “the people”, and all the framers felt that the “whole body of the people” had to be consulted at some point to make their revolution legitimate—but the entire purpose of the Constitution was to ensure that this form of consultation was extremely limited, lest the “horrors of democracy” ensue. At the time, the common assumption among educated people was that there were three elementary principles of government that were held to exist, in different measure, in all known human societies: monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. The framers agreed with ancient political theorists who held that the Roman Republic represented the most perfect balance between them. Republican Rome had two consuls (elected by the Senate) who filled the monarchical function, a permanent patrician class of senators, and, finally, popular assemblies with limited powers of their own. These assemblies selected from among aristocratic candidates for magistracies, and also chose two tribunes, who represented the interest of the plebeian class; tribunes could not vote or even enter the Senate (they sat just outside the doorway) but they were granted veto power over senatorial decisions.

The American Constitution was designed to achieve a similar balance. The monarchical function was to be filled by a president elected by the Senate; the Senate was meant to represent the aristocratic interests of wealth, and Congress was to represent the democratic element. Its purview was largely to be confined to raising and spending money, since the Revolution had, after all, been fought on the principle of “no taxation without representation”. Popular assemblies were eliminated altogether. The American colonies, of course, lacked any hereditary aristocracy. But by electing a temporary monarch, and temporary representatives, the framers argued they could instead create what they sometimes explicitly called a kind of “natural aristocracy”, drawn from the educated and propertied classes who had the same sober concern for the public welfare that they felt characterized the Roman senate of Cicero and Cincinnatus.

It is worthwhile, I think, to dwell on this point for a moment. When the framers spoke of an “aristocracy” they were not using the term metaphorically. They were well aware that they were creating a new political form that fused together democratic and aristocratic elements. In all previous European history, elections had been considered—as Aristotle had originally insisted—the quintessentially aristocratic mode of selecting public officials. In elections, the populace chooses between a small number of usually professional politicians who claim to be wiser and more educated than everyone else, and chooses the one they think the best of all. (This is what “aristocracy” literally means: “rule of the best”). Elections were ways that mercenary armies chose their commanders, or nobles vied for the support of future retainers. The democratic approach—employed widely in the ancient world, but also in Renaissance cities like Florence—was lottery, or, as it was sometimes called, “sortition”.

Sometimes I wonder what the US would look like if our system of representation was based on sortition instead of the current way of doing things, which is largely driven by money, power, and the supposed ‘rule of the best.’ You can read the rest of Graeber’s book online here. Or get yourself a copy of the book.

8) Trending in anthropology

Our of curiosity I wanted to check to see the top trending post on Bluesky for “anthropology.” When I checked on 6/20 the top post was from Daniel Hansen:1

Well, UChicago has paused new PhD admissions in my department now, too. One of the flagship departments for anthropology in the US and worldwide. This on top of hum, social thought, social work, and others. What happens to UChicago’s brand–the so-called “life of the mind”–now? -Daniel Hansen (@danrhan.bsky.social) August 19, 2025 at 10:29 AM

Here’s the top post for “anthropology” from today, 6/24:

Wow: also no PhD admits this year for Chicago’s “anthropology, political economy, social thought, conceptual and historical studies of science, School of Social Work, Harris School of Public Policy”

– David Burbach (@dburbach.bsky.social) August 23, 2025 at 6:51 AM

Both about the same thing happening at Chicago. These are rough times. Keep your heads up folks. We have to find a thousand little ways to keep ourselves going. If all else fails, there’s always Bundt cake! Until next time…

***

- I put “anthropology” in the search bar and shared the result at the top. The results on Bluesky are a bit odd. It’s not totally clear how and why certain results return higher than others. It appears to be a combination of shares and likes (of course), but also heavily weighted by when they were posted. More recent posts, for some reason, return higher than others that have more shares and likes. I’ll look into it. ↩︎

Leave a comment