Editor’s note: This a piece from 2018 that was originally published on Anthrodendum. Slightly edited for clarity.

In the fall 2017 quarter I kicked off my intro to cultural anthropology course with one of those Ancestry dot com videos. These are all over the place, and many of them carry the same basic theme. They all purport to tell people about their ‘family’ or ‘roots’ or ‘heritage.’ That’s fine, except for some of the troubling, misguided messages they send to the public.

The video I showed in class is really short. It’s about a guy named Kyle, who starts off the video saying, “Growing up we were German.” He danced in a German dance group, wore lederhosen, and so on. Culturally, his family was ‘German.’

Here’s where the plot thickens. Kyle then started doing some family research on Ancestry dot com, and wasn’t finding any ‘Germans’ in his family trees. In the background of the video, a graphic displays a family tree with names like Flemming, Ross, and Stewart. Apparently he was looking for German sounding names, didn’t see them, and got to thinking. So he went and got his DNA tested (also via Ancestry dot com). Then the results came back. This is the big moment.

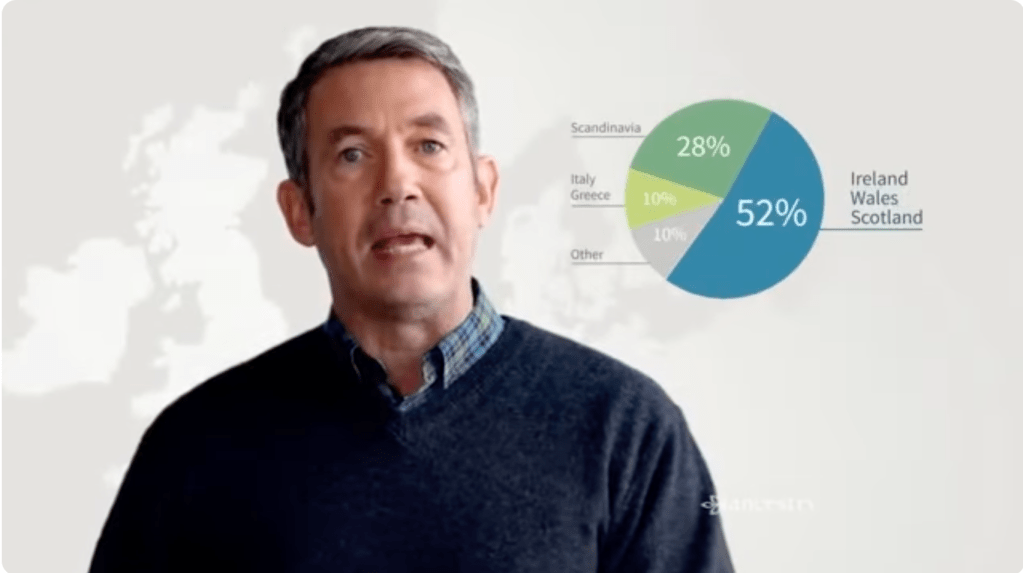

The verdict? Kyle has been living a lie! He found out that he wasn’t German at all! Instead, Ancestry dot com tells him that 52% of his DNA comes from “Scotland and Ireland.” In addition to that, 28% comes from Scandinavia, 10% from Greece and Italy, and another 10% is unknown. This is a game changer for Kyle, and one of the big lines of the video is when Kyle says he decided to “trade in his lederhosen for a kilt.” That’s where the commercial ends. The take home message is basically that these DNA tests tell you who you really are, despite your actual upbringing, cultural practices, family histories, and memories.

This is just wrong.

I understand the fact that people want to research their family histories and find out more about their heritage. Tracing your family genealogy can be fascinating. That’s not the problem here. Kyle’s case is a perfect example of how misguided these tests can be. From an anthropological perspective, one of the primary issues is that these tests seriously conflate culture and biology. The second issue is that these tests paint an oversimplified, if not outright false picture of culture, history, genetics, and genealogy.

To start with the first issue: culture is not genetic. This is a basic, fundamental starting point of cultural anthropology. There is no “Irish” or “German” gene or combination of genes. That’s just not how it works. Culture is shared, patterned, learned behavior. Humans may have the biological capacity for culture, but the specific expression of that capacity is a matter of social relationships and history. This is an old lesson in cultural anthropology, a point that Ruth Benedict drove home in her classic 1934 book Patterns of Culture.

“All over the world, since the beginning of human history,” Benedict wrote, “it can be shown that peoples have been able to adopt the cultures of peoples of another blood” (2005:13). What does this mean? It means that any given cultural behavior is not intrinsic or inherent. As Benedict put it, “Culture is not a biologically transmitted complex” (2005:14). Nobody is born with a certain culture or set of cultural behaviors–people learn it over time (even though, as Bourdieu might say, we tend to ‘forget’ that this has happened). We anthropologists know this. It’s Anthropology 101. Isn’t this old news?

Unfortunately…it’s not. It’s 2018 and this issue is front and center. Our friend Kyle is sort of an entry-level example of a much deeper, more egregious problem. Take, for example, the whole debacle with Kaya Jones (aka #IronEyesKaya), who claimed to be Native American–and therefore qualified to be a “Native American Ambassador” for the Trump administration–because of her genetic ancestry. Jones received a thorough dragging by #NativeTwitter at the end of last year for her attempts to claim Native affiliation. Savannah Martin, who was among those to push back against Jones, highlighted the serious problems of what she called the “quantification of Indigeneity.” Martin clearly delineated the core problems with Jones’ claims:

Lastly, as evidenced by #KayaJones / #IronEyesKaya, the perpetuation of the belief that “blood/stereotypes = identity” permits non-Natives to claim Indigeneity at the drop of a tweet, the purchase of a DNA test, without engaging in the NATIVE aspects of Native identity. (7/n)

— Savannah Martin (@SavvyOlogy) December 27, 2017

In the aptly titled article “Sorry, that DNA test doesn’t make you indigenous” posted on CBC radio, Kim Tallbear explains that Kaya Jones’ attempts to appropriate Native identity are part of a broader pattern:

There is this national sort of story, and this I do see becoming more prominent in certain parts of Canada too, that you have people with no lived experience in indigenous community, they can’t even name any indigenous family or ancestors, but they have a family myth about a Cherokee great-grandmother, or they’re descended from Pocahontas, you get that a lot on Virginia. So I think it’s another kind of claim to own indigeneity, to try to have a moral claim or sense of belonging on the North American continent and so that’s the context in which these tests are so popular.

Tallbear also explains that cultural affiliation extends far beyond the merely genetic or biological: “We construct belonging and citizenship in ways that do not consider these genetic ancestry tests. So it’s not just a matter of what you claim, but it’s a matter of who claims you.” What Tallbear is pointing out is that cultural identity and affiliation are matters of social relationships, not simply biology (let alone some results you get from a main-in DNA test). They are about mutual relationships and histories, not just some fly-by-night Twitter assertions. This is precisely why Kaya Jones’ claims were so strongly rejected, and also why our friend Kyle’s Ancestry dot com results don’t make him Scottish or Irish. Sorry Kyle.

This brings us to the second issue, which is that Kyle’s Ancestry dot com commercial wreaks tremendous havoc on understandings of the relationships between culture, genetics, genealogy, and history. What a disaster. We already have Kyle’s account that he grew up culturally German. If this is true—and not just some embellishment for the sake of the commercial—then it raises a lot of questions. When Kyle got his Ancestry dot com results back, they said that 52% of his DNA comes from Scotland and Ireland, 28% is from Scandinavia, 10% is from Greece and Italy, and another 10% (not a small percentage) was “unknown.” Ok, one thing to realize here is that these tests are based upon a population database. How does this work? Well, as Jon Marks explained in an article written by Barbara King:

They take DNA from people from disparate regions and compare yours to theirs. The numbers reflect a measure of your DNA similarity to those of the divergent gene pools. How do they calculate it? Don’t know; the algorithms are protected intellectual property. Are they accurate? About as accurate as looking in the mirror.

In the same article, King highlights one of Marks’ fundamental points (he explains this more in his book Is Science Racist), which is that these corporations are producing a kind of “fabricated meaning” that is “superimposed” over seemingly objective, raw data. What does this mean? Well, let’s go back to Kyle’s case. When he got his DNA results, he apparently assumed that they meant his family practices were wrong, disproven by science. Kyle read his results to mean that he was mostly from Scotland or Ireland, and therefore culturally Scottish or Irish. This is where Marks’ “fabricated meaning” comes into play. The primary problem here, as genealogist Roberta Estes explains in a very, very detailed article, is that “This technology is not really ripe yet for that level of confidence except perhaps at the continent level and for people with Jewish heritage.” This isn’t the story that Ancestry dot com and others are promoting, of course. What Estes means is that these kinds of DNA tests are only roughly accurate at the continent level, and even then require careful interpretation. Estes explains:

When dealing with intra-continent ethnicity—meaning Europe in particular, comparing one country or region to another—these tests are not reliable and in some cases, appear to be outright wrong.

Kyle’s results, which appear to give him a more detailed understanding of his genetic background, simply cannot be read at that level of confidence. This is due to the limits of technology, but also the realities of human populations. Why? Because humans move, intermix, and generally make the quest to pinpoint any specific ethnic identity on a given geographic population really, really difficult. Kyle was searching for “German” ancestry, but what does this mean? Who were the Germans? Estes asks a great question in her article: “Who or where is the reference population that you would use to represent Germans?” Are we aiming for 2000 years ago? Maybe 1000 years ago? Or 500 years ago? And how does this connect to the reference samples that these companies have today? There are so many variables here, and these mail-in DNA testing companies don’t even come close to addressing them. Again, it’s important to think about migration, war, population mixing and all the fluidities of the human story. It’s all very slippery, complex territory. But again, that’s not the story (or product) that Ancestry dot com is selling.

In Kyle’s case, his results told him that his DNA was mostly Scottish/Irish (aka in the British Isles) and Scandinavian. But who settled the British Isles? A couple of “Germanic” populations come to mind: they’re often lumped together as the “Anglo-Saxons.” Of course this makes any reading of his DNA results much more complicated than his commercial suggests. Not to mention the fact that the “Scandinavian” reference sample—depending on which populations have been used—may be largely indistinguishable from any surrounding “Germanic” population. Remember, these tests are only roughly accurate at the continent level. As Marks puts it, they’re about as accurate as looking in the mirror. So there’s quite a bit of storytelling going on here, a lot of filling in the blanks for the sake of selling DNA tests to eager consumers who want to know “who they are.”

“Heredity,” Ruth Benedict once wrote, “is an affair of family lines.” Beyond that, she argued, “it is mythology” (2005:15). I think she’s right, and it helps to think about how and why we construct these mythologies, and what they mean. I totally understand the reason why people like Kyle would want to learn more about their family histories and discover more about themselves. Who doesn’t want to know more about where they came from? I love learning about this stuff. But there’s a problem when we have companies creating and selling false narratives that claim to clarify these questions, when in fact what they’re doing—at best—is muddying the waters. At worst they’re promoting highly deceptive answers about the past, especially with commercials like the one Kyle appears in.

In the end, if Kyle grew up with all of those culturally German practices, there’s probably a reason for it. I don’t know the story, but something tells me that he didn’t come from Scottish ancestors who arrived in the Americas and suddenly traded in their kilts for lederhosen. I suppose it’s possible, but I doubt it. It’s more likely that Kyle’s family histories and practices were grounded in shared, patterned, learned behaviors that were passed down from one generation to the next. In anthropology, we call this culture. It’s not a biological or genetic thing, and if you’re trying to find out more about it, depending on companies like Ancestry dot com to give you all the answers is not the best plan.

Ok, so you want to learn more about where you came from and who you are. You want to learn about culture. Where to begin? Well, you can always take a cue from anthropologists: A good place to start is taking the time to ask and, more importantly, listen. Yes, I’m talking about asking and listening to people (not machines, or apps, or websites). I realize I’m channeling my inner Luddite here, but sometimes it amazes me just how much we trust technology to tell us everything we want to know about ourselves. Or, even worse, to tell us some truth we want to believe or claim as our own.

It’s important to think about why we search for these answers–and what we’re hoping to find. Are we looking for simple, quick, easy truths? Or are we willing to take the time to delve into it all? Are we open to finding out who we can claim, but also who claims us, as Tallbear put it? In Kyle’s case, he may have gotten a lot further by simply grabbing a notebook and sitting down with a close family member and asking, “Who are we?” That’s just the beginning, of course, but again, it’s a good place to start. Sometimes better answers require more than pushing buttons and swiping credit cards.

References

Benedict, Ruth. 2005[1934]. Patterns of Culture. New York: Mariner Books.

Leave a comment