File this one under the ‘blatant erasure of key historical and political symbols in the name of power’ category:

More than 400 years of history and a decade of advocacy were torn down Thursday afternoon when National Park Service employees removed every single display at the President’s House. 🔗 What’s next? We explain: http://www.inquirer.com/politics/nat…

— Philadelphia Inquirer (@inquirer.com) January 23, 2026 at 2:33 PM

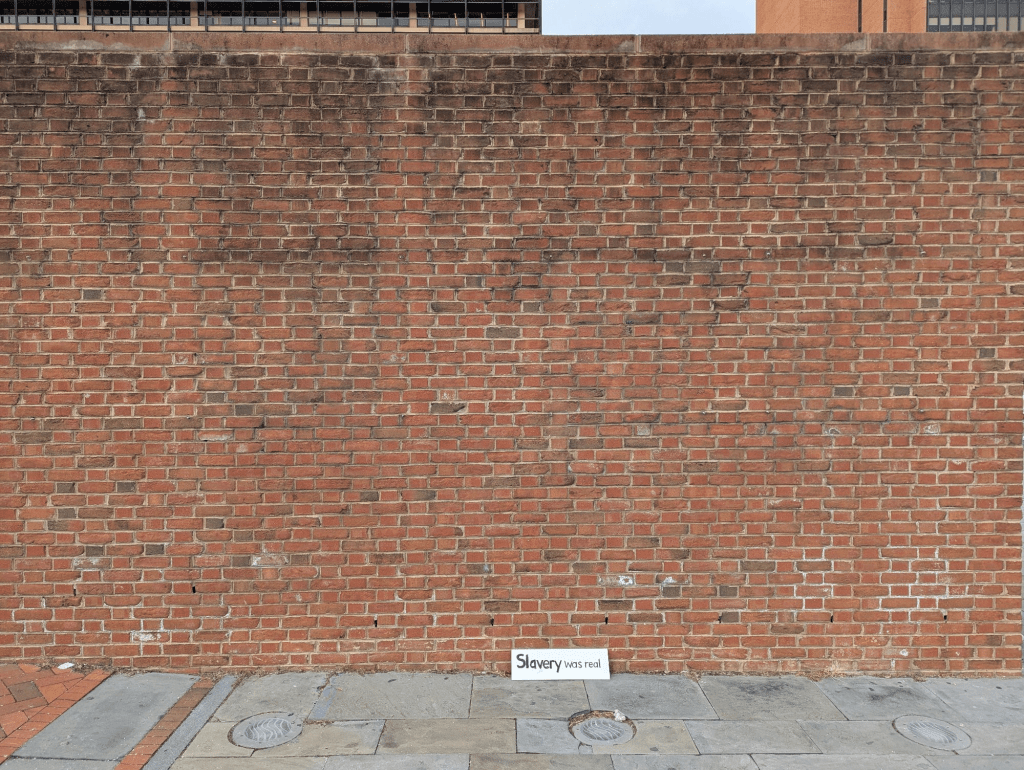

Archaeologist Ben Carter took a photograph of the site after the displays were removed:

A decade ago, there was a whole debate about the subject of removing historical markers and displaying certain flags. That debate centered on the question of removing and tearing down Confederate monuments. There was a 2016 piece in Sapiens about the issue. The author, Richard Handler, wrote:

Whether the statues stay or go is less important than the ongoing conversations they stimulate about the meaning of our national history. As citizens reinterpret this history, invisible markers become suddenly controversial and newly visible. From the subsequent debate—between, for example, those who see in the Confederate flag the sacrifices of their ancestors and those who see in it the seal of an oppressive, racist state—new versions of the American story emerge.

Such debates are less about the ultimate “truth” of history—which is unknowable—than about what we choose to remember, and who we are today. Commemoration is not history; it is about history. It shapes people’s attitudes toward the past and influences what they want to know about it.

One problem, at the time, was the assumption that some of the people involved in those conflicts were actually interested in debates and conversations about history. Many clearly were not.

Handler ended his piece with a kind of hopeful optimism that was, I suppose, still possible at the time:

We need to learn and teach a great deal more about our history of conquest, slavery, and immigration, and examine its relationship to the structural inequalities of the present. These histories are not mere sideshows. They need to be incorporated fully into the story of our country, so we can squarely confront the contradiction between slavery and liberty that Jefferson, for one, so starkly represents. If debates about commemoration lead us to new historical understandings, and new evaluations of today’s world, they will have served their purpose, whatever the fate of the flags and statues that prompted the discussion.

The conversations did not happen. New historical understandings did not emerge. Instead, particularly in the last year, there has been a rapid deployment of state power to erase the histories, narratives, and symbols of what that state sees as its enemies. What happened in Philadelphia this past week is not about ‘truth,’ by any stretch of the imagination. There is no historical dispute about whether or not George Washington owned slaves. Tearing down those signs is an exercise in power.

As the late Michel-Rolph Trouillot wrote in the preface to his book Silencing the Past:

I also want to reject both the naïve proposition that we are prisoners of our pasts and the pernicious suggestion that history is what we make of it. History is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.

Onward, then, to the exposition of roots.

Leave a comment